Who Was Battison?

More about Edwin Battison...

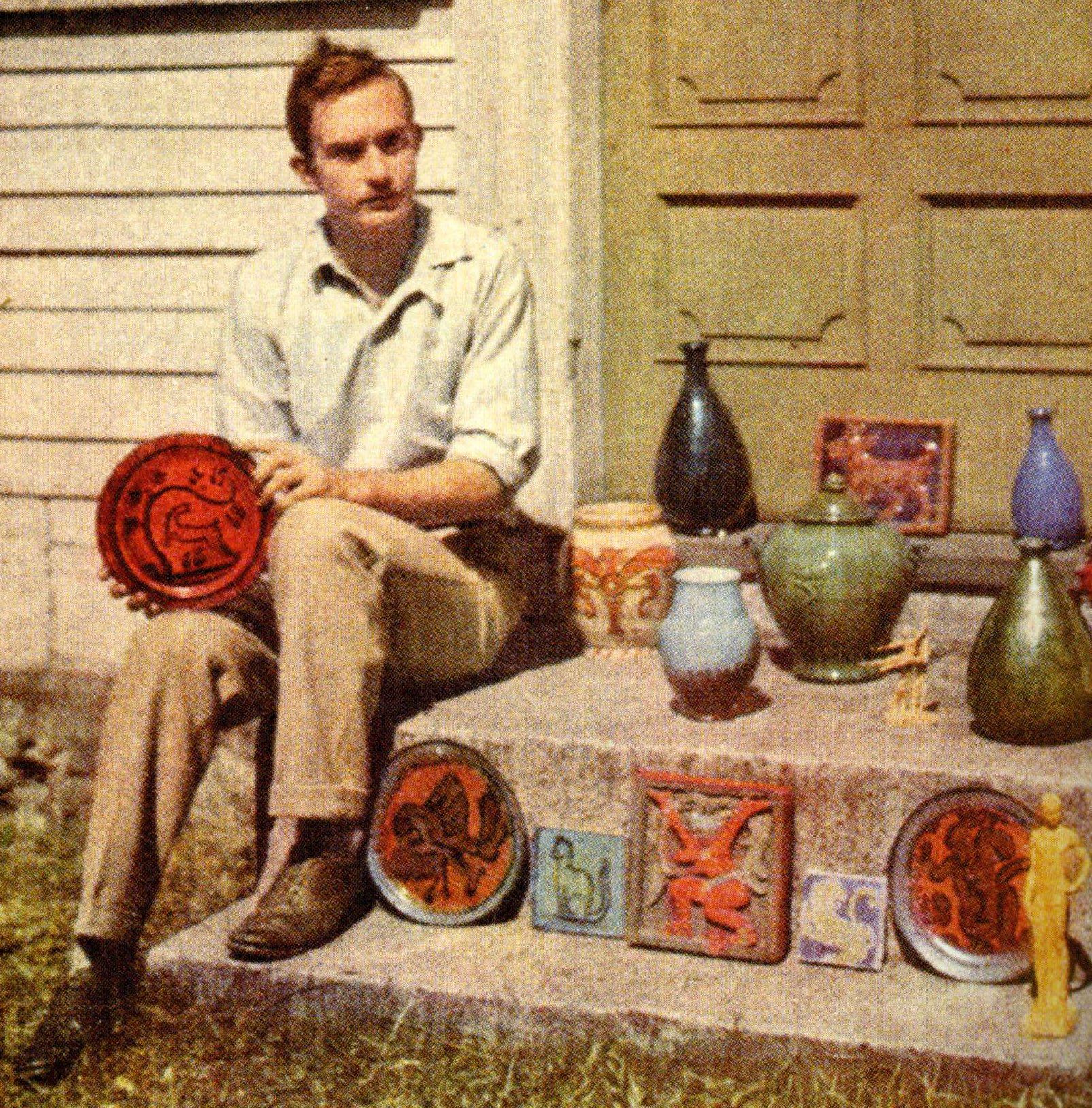

In his teenage days, in a game of “who has found the best," Edwin had fierce competitors in two friends (who became lifelong friends) Maxfield Parrish, Jr. and Paul St. Gaudens. Guns, cars, clocks, watches, machine and hand tools, and steam engines were some of their game pieces. That made him a busy boy in a one-man operation, saving inexhaustible examples from the past. Over the next 70 years, he quietly acquired the finest examples in these and other categories of artifacts.

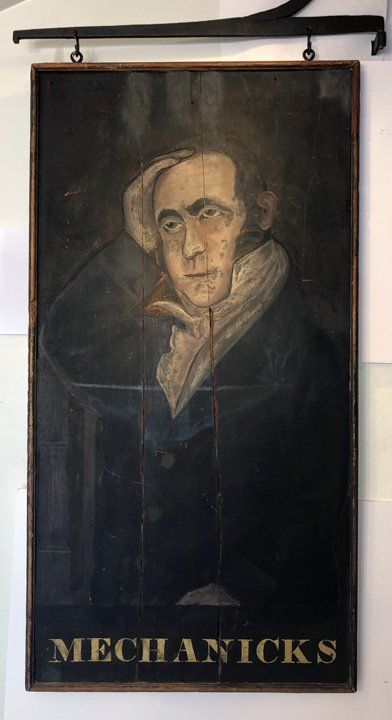

To understand an object, the boy asked questions, penetrating ones beyond his years. “What makes it special?” “Where was it made?” “Was it improved by someone else?" All objects have creators, who in earlier times were called mechanics, an archaic word for inventor. So, Edwin also asked, “Who was its creator?” “Did this person have a mentor?” “What was his family’s history and genealogy?"

In the 1930’s it was a chore to get answers to questions like these- no internet and prohibitive telephone service. Today a few keystrokes can get you more information than you ever care to know. With Edwin, he first queried his family, the old timers, and the town librarian. Looking farther afield, he wrote letters to historical societies, antique and book dealers, and town or city clerks who usually had the skinny on everybody. He wrote to the pioneering mechanics nearing the end of their lives, who, beyond pleased a young man knew of them, answered his questions with details not previously told or recorded. Lastly, the end of the line for research was the Smithsonian, where his questions to the staff were so numerous and revealing that in the next decade, with only a high school education, they hired him as a department curator.

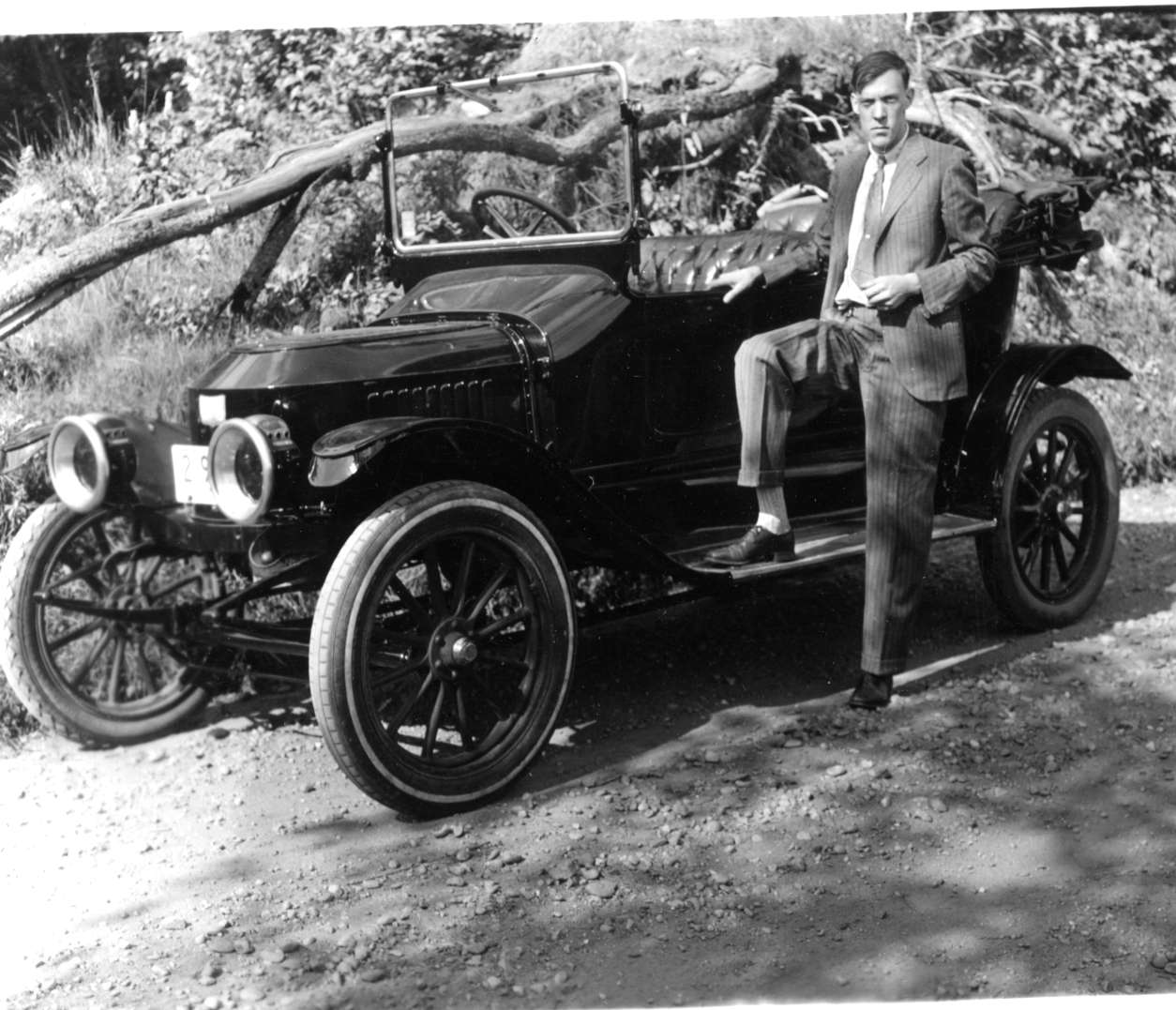

Later in the 1930’s after he bought his first car, he visited creators’ homesteads and shops, their descendants, their neighbors, or shop foremen. Edwin’s earnest and smart manner, flavored with a dry wit, got him through many doors and usually gained him another prized object with its own tale.

The sad part of this story is he disclosed very few of his possessions to anyone when he was alive. He just hinted at their existence to kindred spirits. Why? Maybe because he was a Vermonter in the old style, the type who politely, succinctly and in a droll manner exchanges information with another person, in a measure for measure beat. You tell me then I’ll tell you, but never everything.

Double-sided Mechanicks sign, ca 1810, oil on pine, 61” x 32”, unsigned. A man pondering something clever or unique. Can you help us identify this real person?

Edwin's first steamer

It was true he was very concerned about his artifacts’ security. Everything was under lock and key and important pieces disassembled so as to be unrecognizable, a curse to both thieves and myself. On occasion he subscribed to Gore Vidal’s warning “if you are not paranoid, you are not in possession of the facts,” believing he would do himself a mischief if he advertised his goods.

It was not until just before his death that all his efforts became apparent, but to only one person, this writer, friend, executor, and now chair of his museum. I’m not quite sure why he chose me as it was never discussed. Perhaps I was just the last one left standing. He told me very little about what he had, but I took notes and recorded what he said in 75 hours of audio tapes during our visits at his assisted living and nursing home. This helped me get the lay of his mysterious land. It wasn’t until the third year, in what turned out to be a 14-year organizing and inventory process, that I found the glue that bound each object to its story.

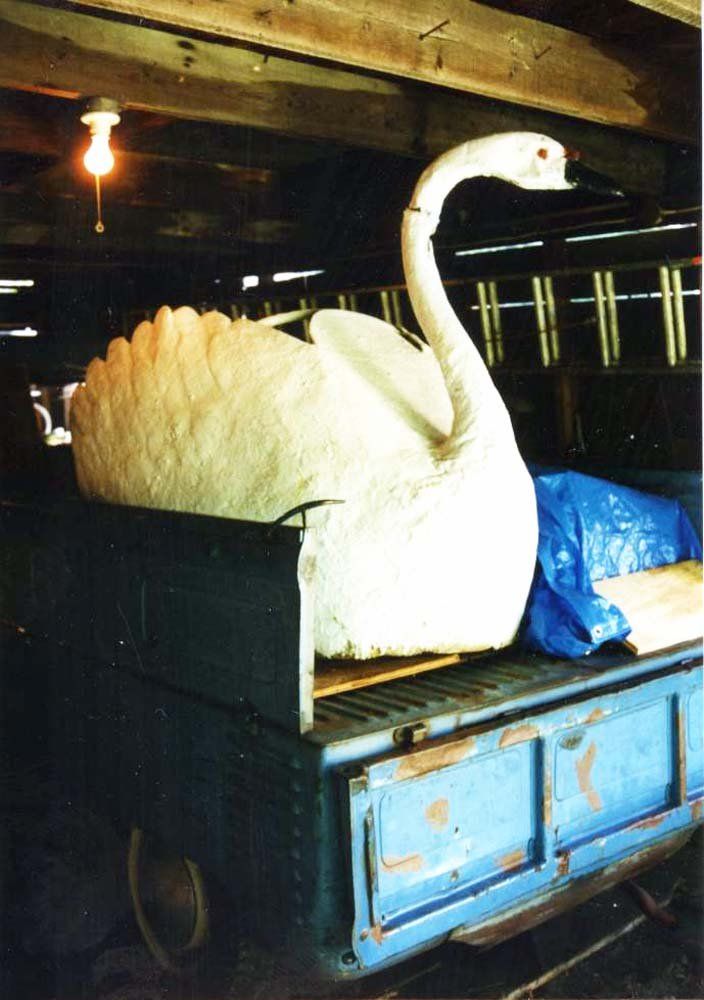

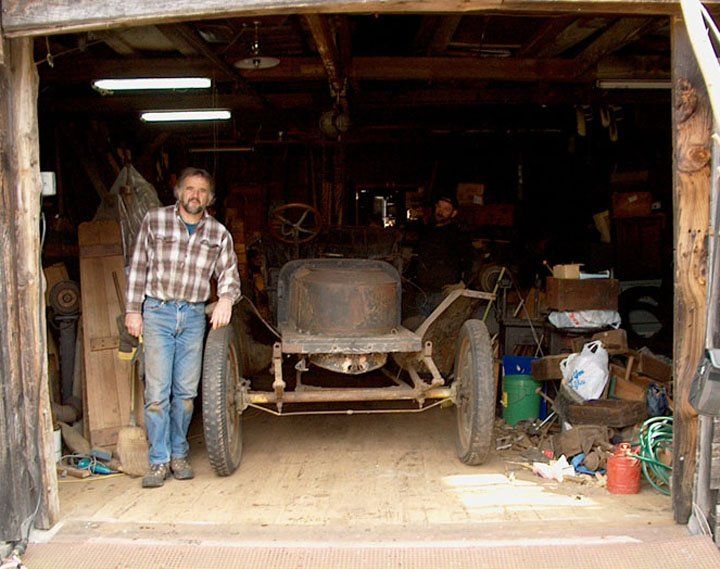

Jay Boeri about to roll out Edwin's 1910 Stanley. It hadn't seen daylight in 30 years and still wears its last issued 1945 Vermont license plate.

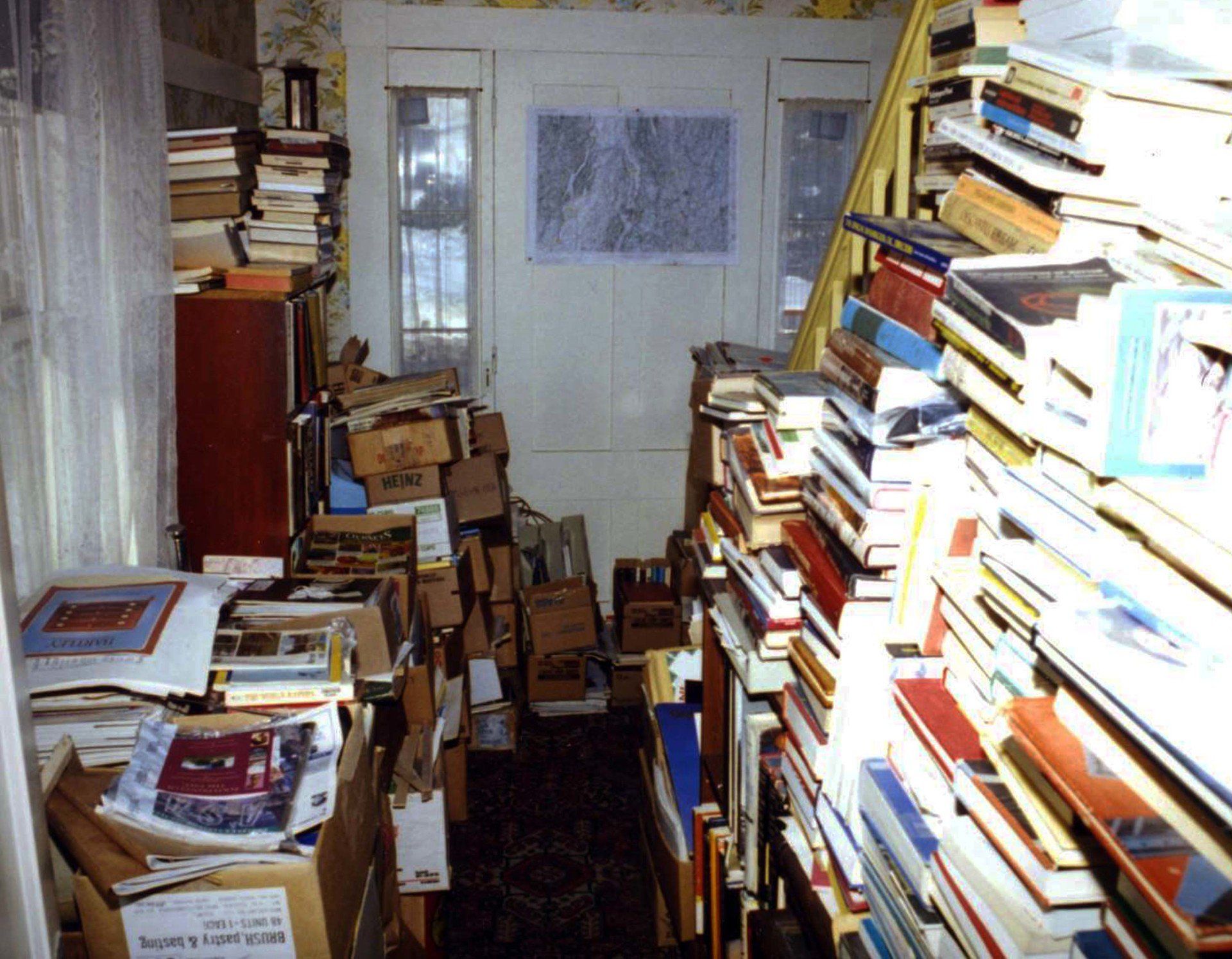

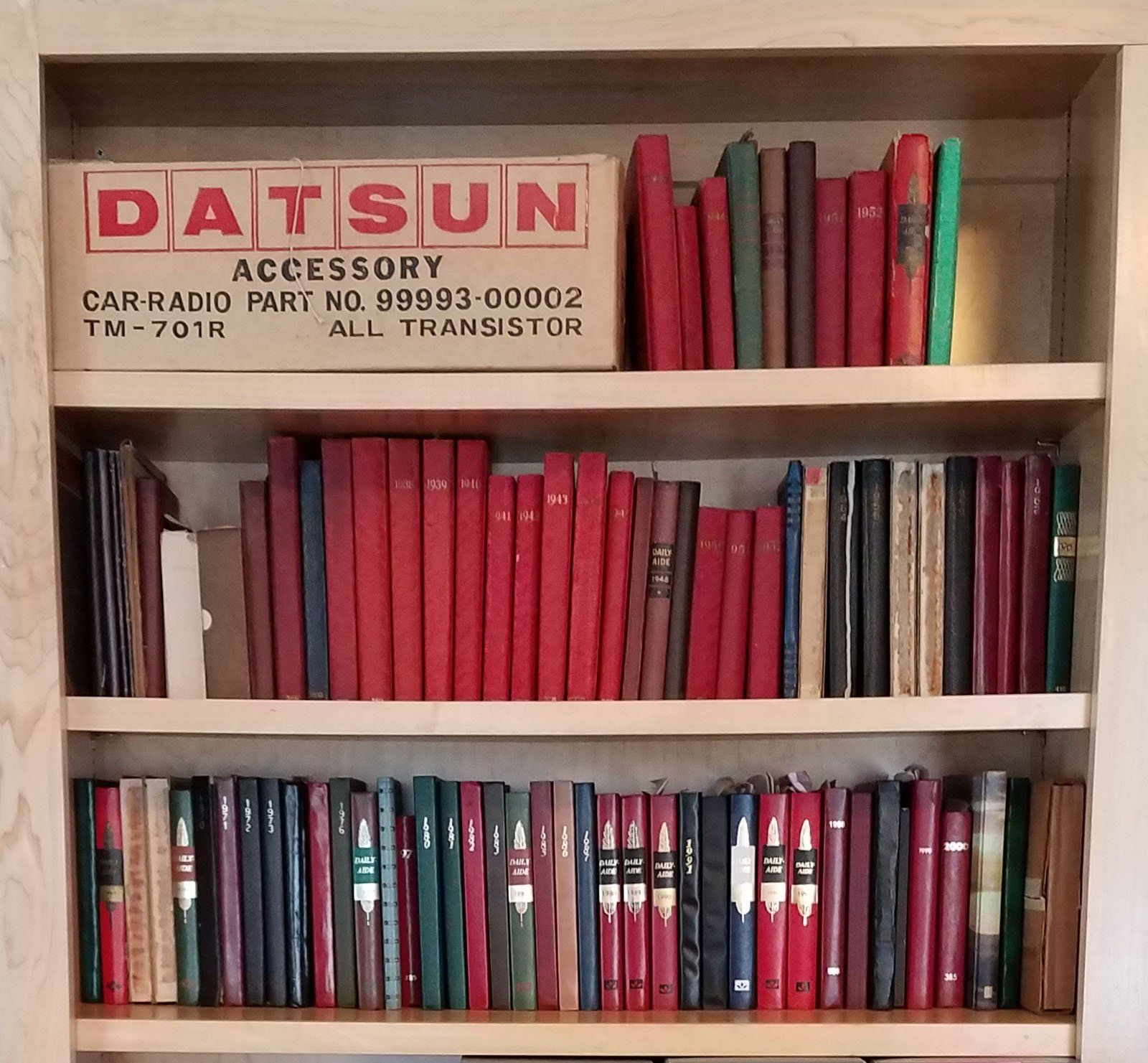

In a box labeled Datsun Truck Parts, hidden in the farthest reaches of his attic, I found 73 years of his personal diaries (1928 to 2000). They contained a stunning insight into the times, people, places, his travels, and the objects of his desire. His anecdotes are wonderful, and there is no guile in his words, just a matter-of-fact outpouring of his observation. It took me 2 years to read and summarize 12,000 entries, and as I did, I heard stories of 500 people who had something special to tell him. What better personal material can a biographer have than 350,000 words of his master’s voice? Complementing his diaries were those of his mother Nellie (Linehan) who died at 91 years. Edwin lived with her all his life. It was sweet to read her words too, to see how she doted on him and he on her.

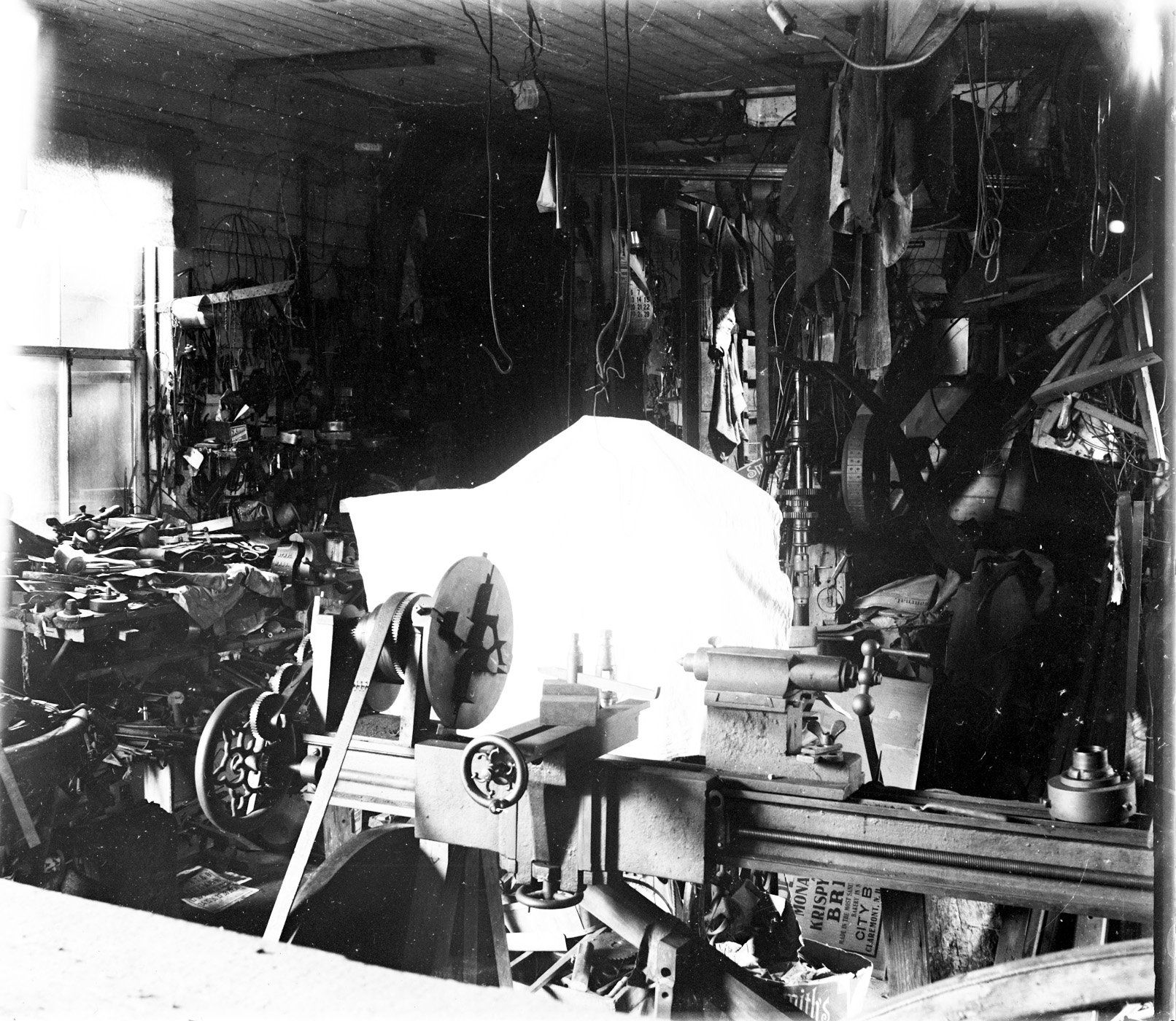

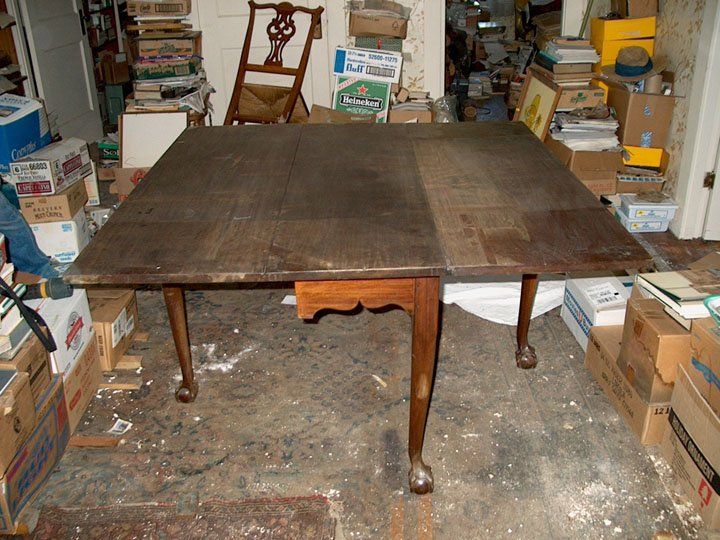

Sadder yet, as I first found them, the objects and their storylines were unconsolidated, strangers to one another. The objects, some gathered 60 years earlier, were laid out in “chronological” order, that is, as discrete piles heaped on top of each other at the precise moment he off-loaded them from his VW truck. The storylines are made whole using his correspondence, research papers, and hundreds of biographies, placed in recycled manila envelopes, names written in pencil on the flaps. He filed them in fancy wooden liquor boxes labeled Drambuie, Jameson, or Cutty Sark that he had salvaged from a nearby Wee-Dram shop.

Edwin's diaries and the box that hid them.

.

Other papers, the good, the bad and the ugly – clipped magazine articles, full plate engravings of DaVinci-like machines from a 16th century folio, grocery store flyers, and his electric, phone, and banking statements - were co-mingled. Placed to overflowing in cut-off cardboard boxes, he randomly stored them in one of five buildings. Make no mistake about it though, he remembered everything he had and where it was stored. The poet Donald Hall could have had Edwin in mind when he ventured that avid collectors should have a box “for string too short to be saved."

Curiosity, not possessiveness, drove him to collect. People motivated by the latter quality he called fanciers as he thought they were more prideful than scholarly. But he was pleased when they came to visit him, silently noting in detail their treasures, doubtlessly for purposes of future acquisition. By contrast were the curious, many of them children, who wrote letters to “Dear Smithsonian Curator” asking questions about their objects. Answering letters was one of his most common duties and one he thoroughly enjoyed. After he provided a tantalizing bit of news, he always ended his letter “Be sure to visit your local library.” He knew from his own experience that he had just launched another explorer, this later evidenced by our trunk loads of thank-you notes and Christmas cards.

The business of how to ask and answer questions was one of Edwin’s hallmarks. His response to a question was one the inquirer meant to ask, not the convoluted one voiced. I always smiled when I saw the questioner frown as he suddenly recognized what had just transpired.

It took 2years to find it, and 3 days to uncover and clear a runway for his 1910 Stanley Steamer. It was his everyday car during World War II, when only kerosene was available for fuel.

Our museum, private and non-profit, is located in an historic district in Windsor, Vermont, a 10-minute walk from the downtown. It’s on a lovely 5-acre site beside Kennedy Pond, the reservoir behind the landmark Ascutney Mill Dam. Each of the 5 buildings in our complex are filled to the brim with rare American objects, papers and 10,000 early photographic images.

.

The History Channel’s American Pickers Show told us our holdings may be “the largest single source, intact, and undisturbed collection in the United States”. Our artifacts are uniquely ingenious, but in a way incidental to our whole story that centers on our sole benefactor and collector of all we own, and his intended mission.

Edwin was the founding director of two museums after his Smithsonian years. He was very proud of the first, the American Precision Museum (APM) in Windsor, Vermont. established in 1967. Its emphasis in his mind was the history of precision manufacturing. The second museum, his expanded thoughts on technology and the sole focus of this story, is the Franklin Museum of Nature and the Human Spirit. The name needs explanation. He tried out many names, some too general, others cumbersome.

Franklin refers to Benjamin Franklin (Edwin is a family descendent), who Edwin believed was the next renaissance “man” following Leonardo daVinci. Nature is the provider of the raw materials necessary to build objects. Nature and the Human Spirit are interlocking elements in the fields of Science, Technology, the Arts and Culture. Exactly what he meant by Human Nature was a little harder to decipher until I found in Edwin’s 5,000 volume library, a special bookmark in Samuel Elliot Morison’s 1930 book Builders of the Bay Colony.

“Even Puritans did not live by faith alone, nor did Puritanism blight the creative and expansive side of human nature. Man’s urge to build and create, his lifelong yearning for comfort and security, his sense of form and beauty, found outlet in early New England, as in few other settlements of like age."

That paragraph seems a timeless description of human nature in its never-ending pursuit to better our existence. It also answers the question of why Edwin told me his museum was “the story of civilizations”, the immediate example being our American one. It was made possible in part by the collective work of all those creators who originated in mid-17th century New England, from where, and over time, they and their prodigies spread their inventive talents across America. They generally worked alone in their small shops with a creaking water wheel for power, clever and industrious as they developed their breakthrough ideas.

By extension, I can’t help but picture a youthful Bill Gates and Paul Allen, and their competitors Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak puttering away in their shops and garages, minus the water wheel, incrementally altering our future. Human nature, like hope, springs eternal.